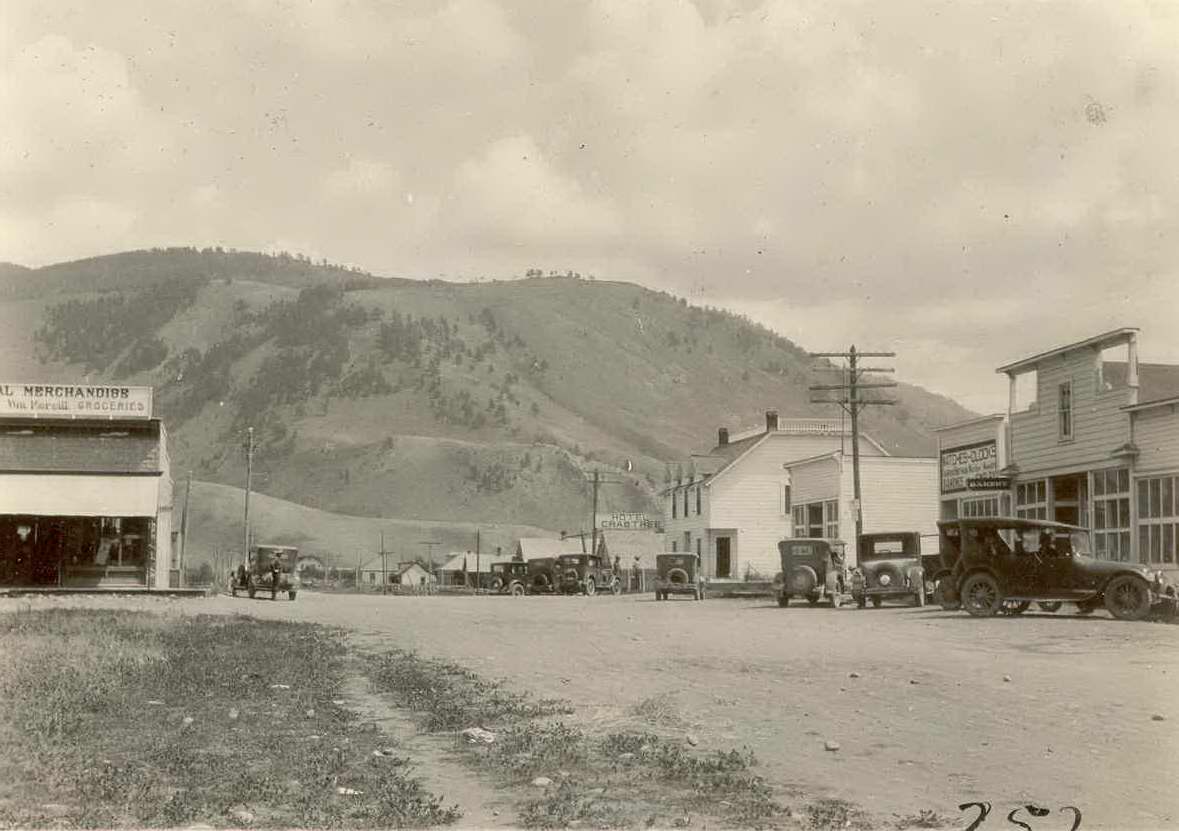

(Credit: Jackson Hole Historical Society / Downtown Jackson, showing Crabtree Hotel, Mercill Merchandise, unknown watchmaker and unknown bakery at the corner of Broadway and Center Street, circa 1920. Photographer: Unknown)

Wyoming was admitted to the Union on July 10th, 1890 and with admission to the Union, became the first state to give women the vote. 2019 marks 150 years of women’s suffrage in the Equality State and has been designated the “Year of Wyoming Women“. Read about a few of the amazing Wyoming women in our tribute to some of Wyoming’s fearless females.

Part I

The Equality State

Wyoming entered the nation on July 10, 1890, as the “Equality State”, recognized as the first state in the United States to grant women the vote, having first done so as a Territory in 1869. The territorial legislature had put forth a bill twenty years earlier, giving women the right to vote; these rights were written into statehood and with that, Wyoming became the state of firsts for many women. The state of Wyoming can claim the first woman elected to a state office, the first woman appointed to Justice of the Peace, the first woman to cast a vote in a general election, the first elected woman Governor to take office, and the first woman appointed to Director of the US Mint.

And now, for the rest of the story… In 1869, Wyoming was short on women, with a ratio of six men to each woman in the state, and something needed to change. Several political issues were at play during this time. It was the period of Reconstruction, post civil-war. The gold rush in the eastern territory had all but dried up. The territory simply needed more women and more families to settle there. By making the territory more appealing to women, the legislature hoped to increase the feminine population of Wyoming and thus garner more votes for the ruling democratic party in the process. After all, they were the political party that would give women the vote and they counted on the women backing the party that gave them the rights.

Meanwhile, John Campbell was a republican governor for the territory with a democratic Legislature. The democratic Legislature, in a power move, decided to put forth a bill for women’s suffrage. The idea was not a new one; several attempts had already failed in neighboring territories and in the US Congress. Women’s suffrage had been a political debate since 1840, losing ground in the years leading up to 1869 because of the shifting focus on voting rights for ex-slaves. Governor Campbell was a supporter of voting rights for ex-slaves, but not, apparently, for women. The democratic Legislature wanted to put a bill in front of him that he would surely veto, thus weakening his stance on voting rights for ex-slaves, an issue that divided the democrats and republicans at the time. (Democrats of the era were generally conservative and did not support voting rights for ex-slaves. Republicans tended to be more liberal, and were in favor of voting rights for ex-slaves.) The democratic Legislature never thought he would sign off on a bill giving women the vote and assumed that with his veto and weakened stance on voting rights, they could win back the governorship for the democratic party.

The bill was introduced by William Bright, a staunch democratic saloon-keeper from Virginia. Rumor has it that his young wife was to thank for his backing of the bill. The bill was hotly debated, with some feeling that it was the right thing to do and others only swaying to back the bill by the fact that the Reconstruction Acts, (the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments), gave black men and Chinese men the right to vote before white women. Governor Campbell signed the bill on December 10, 1869 and even successfully vetoed a repeal attempt by the democrats following the bill’s passing. In 1870, Wyoming’s women went to the polls… and voted overwhelmingly republican.

This year, 2019, marks 150 years of women’s suffrage in Wyoming.

Part II

Yellowstone’s Wild Women

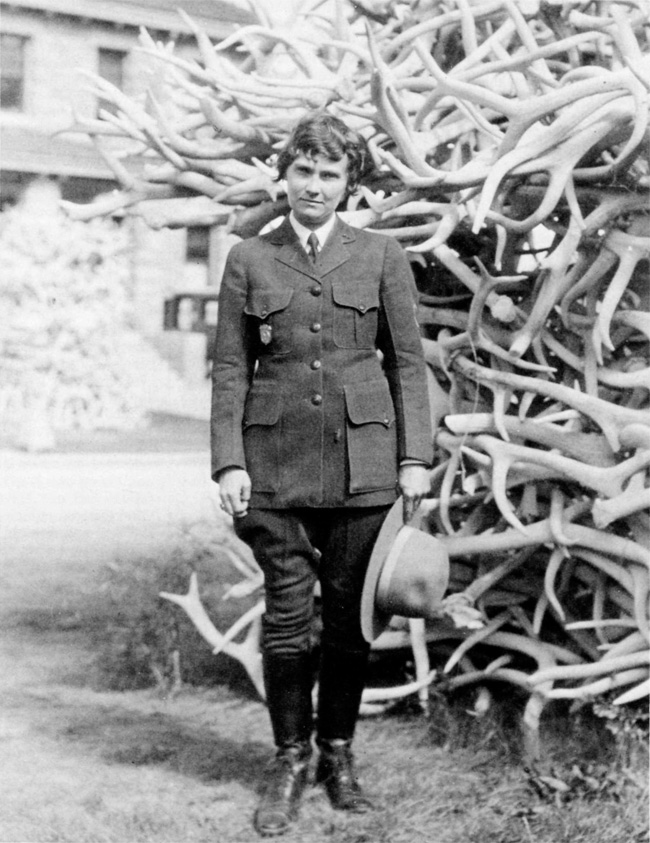

Marguerite Lindsley (1901 – 1952)

Marguerite Lindsley grew up in Yellowstone National Park, her father acting as interim Superintendent while the US Army handed management control over to the National Park Service. Marguerite, educated at home by her mother and in the field by her father, went on to college and obtained a graduate degree in bacteriology. During her college years, she worked as a part time ranger in Yellowstone National Park during the summer months. In 1923, after earning her master’s degree from the University of Pennsylvania, Lindsley quit her job, bought a motorcycle, and headed home to Yellowstone. In 1925, she became the first permanent female park ranger in the country. Uniforms were non-existent and Lindsley had to fashion her own, made to look as much like a ranger uniform as she could. Her homemade uniform became the inspiration for official uniforms for women, but women would not receive an official uniform until more than 20 years later and they would still only have one option for a uniform compared to the men’s three.

Herma Albertson Baggley (1896 – 1981)

Herma Albertson was born in Iowa in 1896 and would become the first female park naturalist in Yellowstone National Park. Baggley enrolled in the University of Idaho and in 1929 was awarded a master’s degree in Botany. She took a summer job at Yellowstone National Park as a “pillow puncher” at Old Faithful Lodge. She helped build the first nature trail at Old Faithful and was the only guide on this trail for three years. She was also a relief lecturer at the lodge. She was known for her engaging talks and samples of wild flowers. In 1931 she was offered a permanent position within the National Park Service as a Naturalist, which she accepted. The first summer of her employment, the superintendent of the park did not allow her to perform naturalist duties, instead providing her only with stenography work for an entire season. This news of this gross misappropriation of personnel reached the previous superintendent Horace Albright. After hearing of her circumstances, he sent a letter to Roger Toll, acting Superintendent of Yellowstone National Park, asking him to put her to work in her field immediately. She worked as a ranger-naturalist until 1933. Baggley co-authored a 1936 publication, “Plants of Yellowstone National Park”, still in use today.

In 1926, Lindsley, a permanent ranger, and four other women were on duty as rangers in Yellowstone National Park. Chief Inspector Gartland was making the rounds through Yellowstone National Park, on assignment from the Department of the Interior. His official report did not favor women in ranger-naturalist positions, stating that naturalists and nature walks within the park would serve to feminize the ranger staff. This was a time of shift within the Park Service as the federal government took over from military oversight in the parks. The naturalist programs were taking off and the park service wanted them to be successful, but the opinion at the Department of the Interior was that a perceived effeminization of the program could sink the popularity of the program. Gartland preferred male rangers to give talks from horseback, highlighting grizzly bears and feats of strength, echoing war stories of the US Cavalrymen from the Civil War. A park ranger should have a formidable presence, in his opinion, and a woman had neither the voice nor the eloquence to do this. He did make mention that Lindsley did have excellent lecturing skills and she was the exception from these remarks. Not everyone agreed with this old fashioned line of thinking, but ultimately the lack of living quarters for women rangers would give those in power the excuse they needed to restrict women from the permanent ranger staff. When Herma Albertson Baggley ended her employment with the National Park Service in 1933, it would be another three decades before the National Park Service again utilized women in permanent ranger roles.

It has been nearly 100 years since the first women rangers made their mark on history. Today, women make up around 37% of the National Park Service workforce. In 2016, the year of the National Park Service Centennial, issues of widespread sexual harassment and retaliation were surfacing throughout the National Park system, punctuated by a breaking story concerning the River District of the Grand Canyon National Park. During the same year, the National Park Service issued a “zero tolerance policy” on sexual harassment but was instantly criticized for not taking allegations of sexual abuse seriously. Sexual harassment continues to be a contentious issue for the National Park Service as they work through several allegations of abuse at several parks across the United States. Sally Jewell, Secretary of the Interior in 2016 aptly described the few cases in 2016 as the “tip of the iceberg”.

Gender does not dictate the success of a ranger. Passion for our natural treasures and a desire to protect them for the enjoyment of future generations does. Children of all genders deserve to see their role models wear a ranger uniform; this will inspire the next generation of National Park Service Rangers. The National Park Service has a duty to uphold a zero tolerance policy and it will be up to local park officials as well as high ranking officials in Washington, DC to uphold that policy with integrity. The future of the National Park Service will depend on it.

Part III

Petticoat Rule

Nearly 100 years ago, the small town of Jackson, Wyoming made headlines across the nation with an unconventional town government, including a mayor, town council, town clerk, town treasurer, health officer and marshal, all of whom were women. In 1920, Jackson Hole had just over 300 residents. The harsh winters and the remoteness of the valley had created a period of slow growth for Jackson Hole compared to other homesteading sites across the west. Because of the unforgiving landscape, residents of the valley had also naturally abandoned traditional gender roles because homesteading didn’t have time for gender roles. Women mended fences and men mended socks and vice versa. It was a question of survival, not propriety.

In 1920, residents had already begun to complain that the town was not adequately collecting taxes, that the roads were not being kept up, and that livestock was free to roam town, with ordinances not being enforced. While it was not the first female town council in the country, the election itself was notable, with an all-women slate running against an all-men contingent. Grace Miller was running for mayor against Fred Lovejoy. Rose Crabtree and Mae Deloney ran for two-year council terms against Henry Crabtree and William Mercill. Genevieve Van Vleck and Faustina Haight ran for one-year council terms against M.E. Williams and T.H. Baxter. The highlight of the election was the square off between Rose Crabtree, nominated for a two year town council term, running against her husband, Henry Crabtree, nominated for the same. The women won handily, garnering almost double the votes of the men in some cases.

Once the mayor and town council were in place, they also nominated women to government posts, with Marta Winger as the town clerk, Edna Huff appointed as health officer, Viola Lunbeck as the treasurer and Pearl Williams as the town marshal.

The women immediately got to work cleaning up the finances and the town itself. They collected all the back taxes and fines that were outstanding and grew the town’s coffers from $200 to $2000. With the money collected they made improvements around town, putting in culverts to divert water from the roads, passing ordinances that criminalized littering, instituting town clean-up, installing electric lights at the town square and refurbishing the cemetery access road.

At the next election in 1921, Miller, Van Vleck and Haight all ran for re-election and bested their male counterparts 3:1 this time in votes counted. This affirmed their work and ensured another year of petticoat rule.

Grace Miller : Mayor

Grace Miller arrived in Jackson Hole in 1893 with her husband Robert. They homesteaded in the area that is the Elk Refuge today. In 1897, Grace purchased land south of their homestead, envisioning the site as a future town. By 1900, there was a saloon, a gun club, a mercantile and a post office. Her vision was taking shape. The Millers were prominent town residents and Grace became mayor in 1920, heading up the all-women government that made national headlines. She served two terms as Mayor of Jackson. She passed away in 1930 at 40 years of age.

Rose Crabtree : Town Council

Rose Crabtree and her husband took over operations at the Reed Hotel in the center of Jackson in 1917. It later became the Crabtree Hotel and Rose and her husband Henry were owner-operators. The original building was torn down in 1990, but the building that sits there now is a replica of the original. Rose passed away in 1978.

Mae Deloney : Town Council

Genevieve Van Vleck : Town Council

Genevieve Van Vleck came to Jackson from Michigan. She married Roy Van Vleck and she and her husband operated the first general store in Jackson. Her house in town was significant at the time because it was the first house in the area to have a well, supplying many neighbors with water. She lived in the house from 1911 to 1960. The house still stands today and is occupied by Cafe Genevieve, a local restaurant.

Faustina Haight : Town Council

Known as “Fannie”, Faustina was born in Emerson, Iowa in 1876. She married Don Haight in Jackson, WY in 1918 and died at the age of 96. Fannie was a teacher in Nebraska, and headed to Jackson, WY with a colleague in 1902 to teach. She claimed a homestead and built herself a log cabin near the Gros Ventre River ca. 1906.

In a recorded transcript of her life, Fannie talks about homesteading in Jackson Hole in the early days:

At the time we entered Jackson Hole, we did not know how long we would be there, but eventually it was three years. In that time my neighbors and friends suggested that I take a homestead. They were glad to have new settlers come in, making new neighbors. So I did. I filed on 160 acres north of Gros Ventre and lived on it with a friend of mine, a girl friend. She came most of the time with me. Of course, I proved up on it later. As I needed a place to live, of course, I built a log cabin. It didn’t cost much. I think the logs cost me $33 and that was about the only cost that I had. Everybody was so generous with their labor and their help. I lived there and taught the school.

Marta Winger : Town Clerk

Marta Winger and her husband moved from Iowa to Jackson Hole 1913 and started a homestead.

In a letter from 1981, Marta recalls her time as town clerk: “Going back to the Women’s Town Council, I don’t really know how it came about or why. My recollection is that it was not in protest to former administration, nor, really, a matter of politics, but just an impulsive and spontaneous gesture on the part of an assembled town caucus, to give the women a chance to run things. It was a very small town, and I remember the delight everybody felt when the event met with such enthusiasm from the press and papers all over the country carried the story. The ladies were besieged by investigating reporters — and Jackson was on the map.” (Letter to Jean Stewart, August, 1981 : On file at the Jackson Hole Historical Society)

Edna Huff : Town Health Officer

Edna was first trained nurse to arrive in Jackson. She and her husband (the first physician) arrived in the valley in 1913.

Viola Lunbeck : Town Treasurer

Pearl Williams : Town Marshal

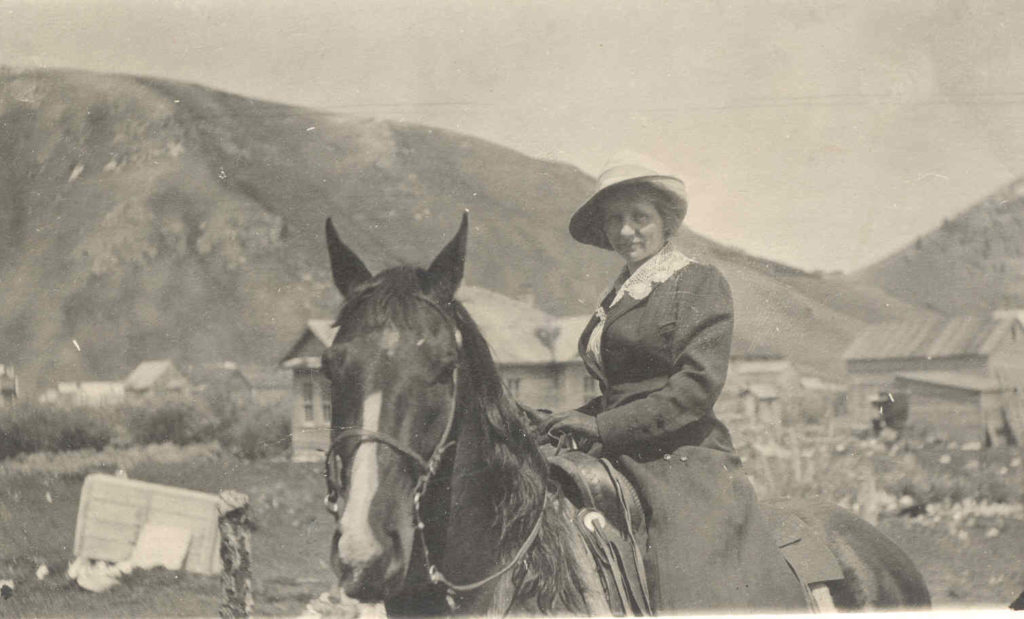

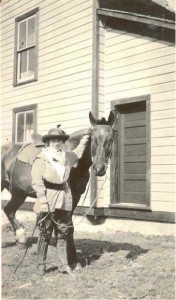

Pearl Williams grew up on a homestead near what is now Highway 22. The youngest of six children, with five older brothers, Pearl was quick to learn how to fend for herself. She was an expert horsewoman and a skilled marksman. Grace Miller appointed her to Town Marshal in 1920, when Pearl was just 22 years old. She was so effective at her job that she resigned in 1921, citing a lack of work. In an interview with a newspaper, she told a sensational story of killing three men and burying them herself as the deterrent for trouble, but the truth was that the all-women’s government of Jackson Hole had things running fairly smoothly. Pearl went back to work at the drugstore, where she was known around town as the “soda squirt”. She married John Hupp in 1927 and raised her family in Montana. She passed away in 1994.

A very special thank you goes to the staff at the Jackson Hole Historical Society who helped facilitate research and provided historical recorded interviews and photographs for reference. Help support their programming so we can keep history alive in Jackson Hole.

Sources

https://www.nps.gov/yell/blogs/a-wildflower-in-yellowstone-herma-albertson-baggley.htm

https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/sontag/baggley.htm

https://www.nps.gov/yell/blogs/herma-albertson-baggley-1896-1981.htm

https://www.doi.gov/blog/trailblazing-women-interior

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marguerite_Lindsley

http://www.montana.edu/president/universitywomen/extraordinary/eow_profiles/lindsley.html

https://www.nps.gov/yell/blogs/marguerite-lindsley-the-first-permanent-female-ranger.htm

https://www.yellowstone.org/women-in-yellowstone/

https://www.wyohistory.org/encyclopedia/right-choice-wrong-reasons-wyoming-women-win-right-vote

http://www.wyo.gov/about-wyoming/wyoming-history

https://jacksonholehistory.org/founding-females/

https://books.google.com/books?id=yZ88rCE0Il4C&pg=PA79&lpg=PA79&dq=irene+wisdom+yellowstone&source=bl&ots=7_zl-KJkwj&sig=ACfU3U0jMFn0an_ac3Cfe69QoNhkLv3vCw&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjf-7Pwu7LhAhVS4VQKHQFeBtoQ6AEwA3oECAgQAQ#v=onepage&q=irene%20wisdom%20yellowstone&f=false

https://www.nps.gov/articles/breeches-blouses.htm

https://www.jhnewsandguide.com/special/centennial/article_899794cb-ab18-5ef7-9ee7-a7df72fc589d.html

http://jacksonholemagazine.com/jacksons-whole-history/

https://www.jhnewsandguide.com/special/jackson_hole_woman/article_030bc2f8-7ac6-51e2-aa67-ea6a43b4b6cb.html

http://westernamericana2.blogspot.com/2009/12/lets-elect-women-jackson-wyomings-all.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Women_in_the_National_Park_Service

https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/grte2/hrs13.htm