Guiding is the imperative to lead people into an environment unknown to them and offer them a personal, in-depth experience of that environment. It is non-specific to gender, age or status.

The Rich Legacy of Western Wyoming Women

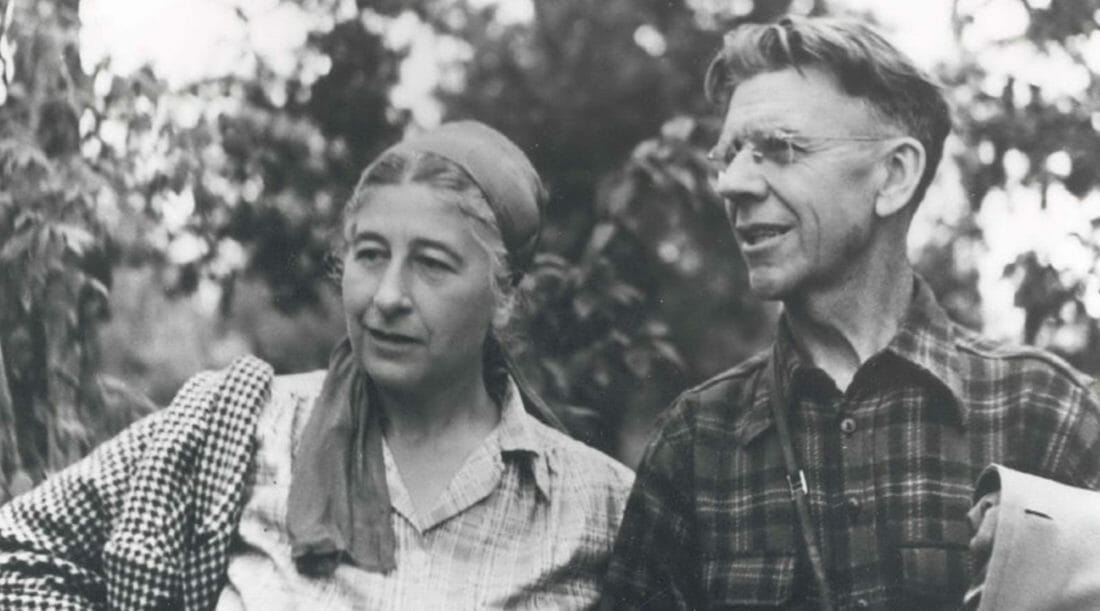

As a professional female wildlife guide, I often speak with my guests about the experience of being a woman and a wildlife guide in the west. I like to talk about the early days of Jackson Hole, when our forward-thinking ladies built the first all-women’s town council in the country. I emphasize the monumental fact that women were given the first right to vote here, many years before the national suffrage movement. I like to quote ground-breaking naturalists like Margaret Murie and Terry Tempest Williams who came to explore our wild places, giving us their incredible observations, research and insights. I especially like to tell the story of hard-edged homesteaders who came to this valley with hefty servings of grit, including standouts like the female-led big game hunting operation at Triangle X Ranch. Those ladies’ trophies still adorn many an honored place over local mantels.

I also draw attention to modern-day noteworthy women, the countless unbelievable athletes who ski, climb, mountain bike, trail-run, hunt, and fish. And I always make a special point to mention the women who steward our National Parks, Forests and Recreation areas, and those fighting for conservation and preservation of those public lands.

Is there Equality in the Equality State?

Yet here in the “Equality State”, there are glaring gender disparities. They are apparent in many industries, and guiding is certainly one of them. Is it possible that the collective resistance to trusting women with traditionally male roles is to blame? We can see this on the home-front, the difficulty in attracting women to a male-dominated field, or even in the visitors to our National Parks, who are enthusiastic about the kindred spirit they believe they share with Wyoming and western life, an unintentional romanticizing of manifest destiny and its accompaniment of antiquated gender-role beliefs, which I am always surprised to see alive and well. The belief that women are as capable and knowledgeable as men in the realm of the wild is still wavering.

All guides make a pledge to adhere to the regulations and mandates which are in place to protect our National Parks. We are colleagues and compatriots with federal and private entities who share the same goal of protecting the sacred lands we all hold dear. As professionals, we are trained to be objective and non-judgmental with each other and our guests in order to offer the safest, most enjoyable experience. For men, those courtesies are given by image alone. A nametag, a uniform; these items communicate knowledge and expertise instantly and respect is granted accordingly. For women, the challenge is to gracefully navigate a man’s world where our abilities must be proven before we can be respected and trusted in the field.

Listen To The Guide

June, 2019 : Grand Teton National Park

It was a perfectly still morning in Grand Teton National Park. A mid-morning light was melting frost on the newly leafed trees, shrubs and grasses, and the smell of sage and pine were heavy on the wind. The sun shone sweetly, and we were in high spirits in our van. I was accompanied by two married couples, friends on vacation together for the first time to Wyoming, all looking forward to a day full of wildlife. We’d had a boomer morning so far, seeing coyote, fox, moose, elk, deer, bald eagle, beaver, ducks, swans and geese all in about an hour and a half after leaving Jackson. We were searching then for an even larger prize; the grizzly.

We ventured into an area where a well-known sow and her cubs had been spending time hunting elk, and after barely a minute we were forced to a stop. 50 or so red taillights glared back at us. I rolled down my window, slowed my breath and listened with my whole body to get a feel for what was happening outside. I could sense a large animal close by, which was reaffirmed by rising excitement in the van and in the energy of the tourists ahead.

Sure enough, a moment later she emerged, a large sow grizzly with a very blond face standing up on her back legs reaching a height of 6, maybe 7 feet. She was merely 10 yards from a handful of people, or it could be said, that they were that close to her. I knew I had to act, as this was an immediately dangerous situation. I saw no Park Ranger or Wildlife Brigade present. In this scenario, guides often take it upon ourselves to monitor and even control a situation to keep bears and humans separate. I asked my guests to stay in the vehicle while I got out. The situation was tenuous.

There were around 100 people gathering close to the bear now.

“Everybody please back up!” I yelled out to the crowd. “That bear is very capable of injuring you to protect her cubs. Please back up! It is not safe. Park policy states that we need to remain 100 yards from bears!” I said earnestly, to no reaction. I approached, holding my bear spray high enough to be seen by all. I was wearing professional outdoor clothing with my company name on my jacket and hat, as well as a name tag.

As soon as I entered the crowd there was commentary. “I don’t have to listen to you,” said one man. “You’re not my mother,” said another. “Go away b***h. This is a once in a lifetime pic,” sneered a third. “You’re not a ranger,” they said. “You’re not in control of me. What do you know lady?!”

The comments went on and on and on. I could feel my blood pressure rise and my need to stay calm imminent. But, the crowd would not listen to me.

I jostled my way to the middle of the road and attempted to move the traffic that had stalled around the bear. I knew this bruin, and I knew she was used to paparazzi, but separation is more important than fame. I found myself, like all my colleagues have at some point, in a position between the bear and the crowd. I was too close to her, exposed, and absolutely alone. My heart was racing and my body was on complete high-alert. I was aware of the need to consciously calm my system, as bears can easily react to this kind of frantic energy. Regardless of the personal, emotional turmoil, there I was, ready to face a 600-pound bear for the safety of strangers, and nobody seemed to care. I couldn’t help but feel angry, wronged, and belittled.

My rational mind offered relief; maybe these people were just so excited to see a bear that all good decision-making went out the window!

In that moment a man appeared, middle-aged with a salt-and pepper beard, dark sunglasses, full ranger regalia, hands on hips where a gun was clipped. “Folks, everyone needs to back up now!” he yelled in a deep, serious voice. Immediately the crowd dispersed. People raced into their cars, traffic picked up again, and even the bear started to lumber away. (I caught sight of her two cubs, which had been hidden the whole time behind a stand of tall sage). He looked at me and said, “get back to your car ma’am,” as if I had been just as much of an interloper as another ignorant tourist.

The Invisible Barrier for Wyoming’s Wild Women

Most women guides would find themselves nodding in agreement here. Being summarily dismissed is just part of the job. Is it surprising that women only comprise about 20% of the workforce as wildlife guides? It raises the question many women face: how do we garner trust? The women I know who guide professionally are proud and passionate, and make a concerted choice to assume a leadership role in the wilderness. It takes courage, fortitude and resolve to make this decision.

Our guests have the privilege of spending the day with amazing guides. Our female colleagues are ardent in their efforts to be the best they can be. They work well with their colleagues and are totally self-sufficient. They are well versed in geology, biology and other natural sciences. They know how to make something small and seemingly insignificant come alive for their guests. They overlook the constant questioning of their knowledge, and share everything they know. They use their intuition to guide conversation, interests and attend to the personal needs of their guests. They navigate incredible winter storms and horrific road conditions with grace. They carry spotting scopes, binoculars, backpacks, and bear spray up pebbled hills, across soggy marshlands, and through dark forests to find the best vantage point for guests to observe an animal. They are the consummate professional.

They track and find grizzlies, even when they are told that grizzlies are too dangerous for a woman.

Women are patient; women are kind, but women are not one-dimensional. They carry the same essential desire for connection with people, the exploration of knowledge, and deep love for the wilderness, as every other guide out there.

Wildlife and Wild Spaces are for Everyone

The equalizer we may be looking for is this; that a love of wilderness is in fact suited to all people, and all people are allowed to be both participants, and leaders.

Are we shaping a future that allows for female wildlife guides? Will we support women in roles of leadership? Maybe we can change our collective opinion of current life in the west. Maybe we can begin to trust the process of hiring qualified people while truly being unbiased for gender. Maybe we can allow women to be strong, brave, knowledgeable and capable. After all, guides are all looking to share the same experience, and our credentials far surpass our gender. The many hats that professional female wildlife guides wear on the job include, but are not limited to; educator, advocate, liaison, translator, interpreter, specialist, expert, naturalist, first-responder, tracker, historian, story-teller and proud Wyomingite.

At the end of the day, we all deserve to be respected for our talents and our skills. After all, a grizzly doesn’t care whether you’re a man or a woman. If you’re an unskilled guide, you’ll know soon enough.